| EDWARD "ED" DAVIS (THE FIRST AFRICAN-AMERICAN TO HEAD DETROIT'S AILING BUS SYSTEM) |

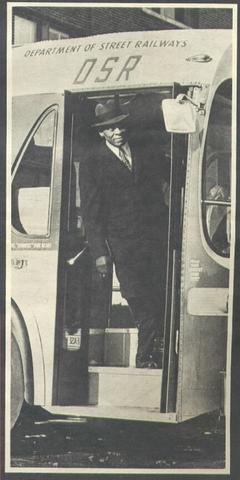

In the fall of 1971, Edward "ED" Davis would become the first African-American to be

appointed as general manager of Detroit's Department of Street Railways (DSR). But

prior to his new job as head transit chief, he enjoyed a long and successful ground-

breaking career in the automobile sales industry. During his thirty year career in the

automobile business, Davis would become the first African-American to own a used-

car dealership in the U.S., the first to be awarded a new-car franchise, and in the fall

of 1963, he would become the first African-American to own a Big Three franchise, a

Chrysler-Plymouth-Imperial dealership located on Dexter and Elmhurst in Detroit.

appointed as general manager of Detroit's Department of Street Railways (DSR). But

prior to his new job as head transit chief, he enjoyed a long and successful ground-

breaking career in the automobile sales industry. During his thirty year career in the

automobile business, Davis would become the first African-American to own a used-

car dealership in the U.S., the first to be awarded a new-car franchise, and in the fall

of 1963, he would become the first African-American to own a Big Three franchise, a

Chrysler-Plymouth-Imperial dealership located on Dexter and Elmhurst in Detroit.

ED DAVIS, THE AUTOMOTIVE YEARS:

Born in Shreveport, Louisiana on February 27, 1911, Ed Davis was the oldest of ten children. His mother passed when he

was ten years old; his father–who was a food jobber—owned his own business, which enabled him to earn enough money

to feed, house and clothe his family comfortably. His dad also owned a 500-acre farm located about sixty miles from town.

As a youngster, Davis began to be fascinated with the inner workings of his father's Model-T Ford, which helped to spark

his interest in and love of cars.

At the age of fifteen, Davis convinced his father to allow him to move to Detroit, to live with an aunt, where he could get a

better education than what was offered in the poor black schools in Shreveport. In Detroit schools, he could also combine

his love of cars with a solid business training. He was able to attend Cass Technical High School in Detroit, where at one

time he considered a career in accounting. However, he became discouraged after discovering that the accounting field of-

fered little opportunities for blacks, and instead turned his focus toward his first love–automobiles. To learn more about the

automobile business he took a job part-time in a car-repair garage during his last year at Cass, working for no pay beyond

his 12¢ round-trip streetcar fare. After several weeks he was paid more than transportation money, and eventually worked

his way up to $12.00 per week. However, the Depression of the 1930's would result in the loss of his job.

In 1934, Davis was able to start his own business by renting a car wash business in a gas station. This was after convincing

the owner to allow him to offer this service in his station. Davis' big break would come after one of his car wash customers,

a Mr. Lampkins, offered him a job in the foundry at the Dodge Brothers main assembly plant in Hamtramck. After having

worked there a few weeks, Lampkins—a superintendent at the plant—arranged for Davis to be shifted from the foundry to

a better job in the machine shop. After having recognized Ed Davis' great love for cars, along with his winning manner, Mr.

Lampkins would later offer him a job as a new car salesman—on a 'part-time' basis—at the new auto dealership he had just

arranged for his son. In 1936, Ed Davis began his first car salesman job at the Merton L. Lampkins Chrysler-Plymouth

dealership, located at 16330 Woodward Avenue, in a "high income area" of Highland Park.

Unfortunately, discrimination was a factor of daily life back in those days, and being black, Davis found himself shunned by

his white coworkers. Davis was not allowed to work on the main showroom floor with the white salesmen, but was required

to work out of a secluded makeshift office in the dealership's second floor stockroom. However, Davis was able to use this

discrimination to his advantage. He fixed-up the storeroom into his "private office"—where he brought in his own desk and

office furnishings—and since he had to solicit customers on his own he didn't have to spend time with those who only visit-

ed the dealership to browse. Instead, he was forced to get out into the black community to sell cars. But despite the odds,

Davis was able to establish a growing clientele of loyal customers, and eventually went on to sell more cars than any of the

dealership's white salesmen. Many from the city's black community heard about "the black man who sold Chryslers." Davis

became so successful at his job he was eventually promoted to full-time salesman, but turned down an offer to give up his

office and work on the floor with the others. Meanwhile, hostility toward him from among the sales-staff grew, even to the

point of a physical confrontation with a coworker.

In 1938, Ed Davis decided he was ready to open his own auto dealership. On December 4, 1939, Davis Motor Sales—a

used-car lot—opened for business out of a former plumbing supply building located at 421 East Vernor Highway, which

today serves as the location of the Fisher (I-75) Freeway at Brush. The dealership was located in the city's predominately

African-American "Paradise Valley" community, a few blocks north of Detroit's downtown business and shopping district.

Although the used-car lot sold all makes of cars, and business was good, Davis' main desire was to sell new cars. However,

he did continue on as a new car broker for black customers, and even without a new-car dealership of his own, he was still

able to sell a large volume of new cars. He would later open a Standard Oil gasoline station next door to his dealership.

Born in Shreveport, Louisiana on February 27, 1911, Ed Davis was the oldest of ten children. His mother passed when he

was ten years old; his father–who was a food jobber—owned his own business, which enabled him to earn enough money

to feed, house and clothe his family comfortably. His dad also owned a 500-acre farm located about sixty miles from town.

As a youngster, Davis began to be fascinated with the inner workings of his father's Model-T Ford, which helped to spark

his interest in and love of cars.

At the age of fifteen, Davis convinced his father to allow him to move to Detroit, to live with an aunt, where he could get a

better education than what was offered in the poor black schools in Shreveport. In Detroit schools, he could also combine

his love of cars with a solid business training. He was able to attend Cass Technical High School in Detroit, where at one

time he considered a career in accounting. However, he became discouraged after discovering that the accounting field of-

fered little opportunities for blacks, and instead turned his focus toward his first love–automobiles. To learn more about the

automobile business he took a job part-time in a car-repair garage during his last year at Cass, working for no pay beyond

his 12¢ round-trip streetcar fare. After several weeks he was paid more than transportation money, and eventually worked

his way up to $12.00 per week. However, the Depression of the 1930's would result in the loss of his job.

In 1934, Davis was able to start his own business by renting a car wash business in a gas station. This was after convincing

the owner to allow him to offer this service in his station. Davis' big break would come after one of his car wash customers,

a Mr. Lampkins, offered him a job in the foundry at the Dodge Brothers main assembly plant in Hamtramck. After having

worked there a few weeks, Lampkins—a superintendent at the plant—arranged for Davis to be shifted from the foundry to

a better job in the machine shop. After having recognized Ed Davis' great love for cars, along with his winning manner, Mr.

Lampkins would later offer him a job as a new car salesman—on a 'part-time' basis—at the new auto dealership he had just

arranged for his son. In 1936, Ed Davis began his first car salesman job at the Merton L. Lampkins Chrysler-Plymouth

dealership, located at 16330 Woodward Avenue, in a "high income area" of Highland Park.

Unfortunately, discrimination was a factor of daily life back in those days, and being black, Davis found himself shunned by

his white coworkers. Davis was not allowed to work on the main showroom floor with the white salesmen, but was required

to work out of a secluded makeshift office in the dealership's second floor stockroom. However, Davis was able to use this

discrimination to his advantage. He fixed-up the storeroom into his "private office"—where he brought in his own desk and

office furnishings—and since he had to solicit customers on his own he didn't have to spend time with those who only visit-

ed the dealership to browse. Instead, he was forced to get out into the black community to sell cars. But despite the odds,

Davis was able to establish a growing clientele of loyal customers, and eventually went on to sell more cars than any of the

dealership's white salesmen. Many from the city's black community heard about "the black man who sold Chryslers." Davis

became so successful at his job he was eventually promoted to full-time salesman, but turned down an offer to give up his

office and work on the floor with the others. Meanwhile, hostility toward him from among the sales-staff grew, even to the

point of a physical confrontation with a coworker.

In 1938, Ed Davis decided he was ready to open his own auto dealership. On December 4, 1939, Davis Motor Sales—a

used-car lot—opened for business out of a former plumbing supply building located at 421 East Vernor Highway, which

today serves as the location of the Fisher (I-75) Freeway at Brush. The dealership was located in the city's predominately

African-American "Paradise Valley" community, a few blocks north of Detroit's downtown business and shopping district.

Although the used-car lot sold all makes of cars, and business was good, Davis' main desire was to sell new cars. However,

he did continue on as a new car broker for black customers, and even without a new-car dealership of his own, he was still

able to sell a large volume of new cars. He would later open a Standard Oil gasoline station next door to his dealership.

Meanwhile, it was during this period, that the South Bend, Indiana

based Studebaker Corporation had been struggling to sell cars

in Detroit. After hearing word about the successful Ed Davis, the

company brass decided that Davis might be the way to reach the

city's black population, which could offer tremendous potential for

sales. In 1940, the company offered Davis a Studebaker franchise.

Davis decided to accept the offer. Although no bank would grant

him a loan, he risked his entire savings, and was able to obtain the

$10,000 needed to open the franchise. Davis would remodel his

building, and would soon be in business selling new Studebakers.

With the opening of his Studebaker dealership in the summer of

1940, Ed Davis became the first African-American to be awarded

a new-car franchise in the United States. He would later be elected

president of the Studebaker Dealers Association of Detroit.

based Studebaker Corporation had been struggling to sell cars

in Detroit. After hearing word about the successful Ed Davis, the

company brass decided that Davis might be the way to reach the

city's black population, which could offer tremendous potential for

sales. In 1940, the company offered Davis a Studebaker franchise.

Davis decided to accept the offer. Although no bank would grant

him a loan, he risked his entire savings, and was able to obtain the

$10,000 needed to open the franchise. Davis would remodel his

building, and would soon be in business selling new Studebakers.

With the opening of his Studebaker dealership in the summer of

1940, Ed Davis became the first African-American to be awarded

a new-car franchise in the United States. He would later be elected

president of the Studebaker Dealers Association of Detroit.

|

Interestingly, when Ed Davis opened his Studebaker dealership in 1940, only two blacks in Detroit owned a Studebaker

automobile. So initially, sixty percent of his business came from white customers, but this would drastically change after the

violent Detroit race riots erupted during the summer of 1943. From that point onward, Davis Motor Sales would depend

almost entirely upon its black customers, as service traffic from white customers dropped off after the riots. However, after

gasoline rationing and new car restrictions were lifted after WW-II, the demand for new cars skyrocketed. Studebaker's

share of the Detroit market more than doubled and business for Davis was good. He even had to expand his facilities.

However, by 1953, stiff competition and price cutting from among the "Big Three" would result in major market sales loses

and profit declines for Studebaker—as the automaker faced possible bankruptcy. On October 1, 1954, the Studebaker

Corporation was acquired by the Detroit based Packard Motor Car Company. The newly merged company would be-

come known as the Studebaker-Packard Corporation.

But unfortunately, Studebaker's auto sales plummeted after its 1955 models were introduced. After assurances were made

to Ed Davis by representatives from General Motors, Ford and Chrysler of acquiring a possible new-car dealership with

one of the Big Three, he decided to drop his Studebaker franchise in April, 1956. In June of 1956, a Plymouth-DeSoto

franchise promise fell apart after other Detroit dealers feared they would lose all of their black business if Davis was granted

a dealership.

After promised franchise offers never materialized, Davis has to settle for being a sub-dealer for a local Ford dealer—on the

promise of an opportunity of a Ford franchise whenever the territory around him became available. He became associated

with Floyd Rice Ford—one of Ford's largest Detroit dealers—and was made a vice-president in the firm. He could sell cars

as a sub-dealer through their downtown dealership—located just five blocks from his, at 100 West Vernor. But after Floyd

Rice later closed its downtown location in early 1958, Davis was never offered a Ford franchise. He attempted to continue

on at the Floyd Rice main dealership on Livernois Avenue at Doris—along Detroit's "Automobile Row." But racial prejudice

and anger from the sales staff at that location—even though located in a predominately black neighborhood—made things

unbearable, and in order to keep the peace, his arrangement with the Floyd Rice agency was ended. The major portion of

Ed Davis' business would once again return to primarily selling used cars.

But this time his auto business would suffer a financial blow, after it had been announced that his property was in the path

of a proposed new Detroit freeway. By 1959, most of the area surrounding his business had been condemned and slated

for urban renewal development. The entire area was deteriorating, both physically and economically. Eventually, construc-

tion on the Fisher (I-75) Expressway in Detroit—which tore through E. Vernor street and much of that lower east-side

black community—would force him to close his business. In 1962, the government paid him $75,000 for his property.

automobile. So initially, sixty percent of his business came from white customers, but this would drastically change after the

violent Detroit race riots erupted during the summer of 1943. From that point onward, Davis Motor Sales would depend

almost entirely upon its black customers, as service traffic from white customers dropped off after the riots. However, after

gasoline rationing and new car restrictions were lifted after WW-II, the demand for new cars skyrocketed. Studebaker's

share of the Detroit market more than doubled and business for Davis was good. He even had to expand his facilities.

However, by 1953, stiff competition and price cutting from among the "Big Three" would result in major market sales loses

and profit declines for Studebaker—as the automaker faced possible bankruptcy. On October 1, 1954, the Studebaker

Corporation was acquired by the Detroit based Packard Motor Car Company. The newly merged company would be-

come known as the Studebaker-Packard Corporation.

But unfortunately, Studebaker's auto sales plummeted after its 1955 models were introduced. After assurances were made

to Ed Davis by representatives from General Motors, Ford and Chrysler of acquiring a possible new-car dealership with

one of the Big Three, he decided to drop his Studebaker franchise in April, 1956. In June of 1956, a Plymouth-DeSoto

franchise promise fell apart after other Detroit dealers feared they would lose all of their black business if Davis was granted

a dealership.

After promised franchise offers never materialized, Davis has to settle for being a sub-dealer for a local Ford dealer—on the

promise of an opportunity of a Ford franchise whenever the territory around him became available. He became associated

with Floyd Rice Ford—one of Ford's largest Detroit dealers—and was made a vice-president in the firm. He could sell cars

as a sub-dealer through their downtown dealership—located just five blocks from his, at 100 West Vernor. But after Floyd

Rice later closed its downtown location in early 1958, Davis was never offered a Ford franchise. He attempted to continue

on at the Floyd Rice main dealership on Livernois Avenue at Doris—along Detroit's "Automobile Row." But racial prejudice

and anger from the sales staff at that location—even though located in a predominately black neighborhood—made things

unbearable, and in order to keep the peace, his arrangement with the Floyd Rice agency was ended. The major portion of

Ed Davis' business would once again return to primarily selling used cars.

But this time his auto business would suffer a financial blow, after it had been announced that his property was in the path

of a proposed new Detroit freeway. By 1959, most of the area surrounding his business had been condemned and slated

for urban renewal development. The entire area was deteriorating, both physically and economically. Eventually, construc-

tion on the Fisher (I-75) Expressway in Detroit—which tore through E. Vernor street and much of that lower east-side

black community—would force him to close his business. In 1962, the government paid him $75,000 for his property.

ED DAVIS, THE D.S.R. YEARS:

On October 1, 1971, about seven months after he closed his automobile dealership, Mayor Roman S. Gribbs appointed

Ed Davis as the new general manager of the DSR. At the time, Gribbs had been looking for a prominent black to join his

administration. It was hoped that Davis might discover some innovative ways to improve service at the problem-riddled,

money-losing transit agency. Davis later stated that he took the job as a challenge, and wanted to improve the system.

When Davis took over in October, 1971, the DSR operated 1,100 buses, employed 2,380 people, and generated more

than $200,000 from the fare box a day, or some $150 million a year. But despite those numbers, the department had

lost money every year since 1966, at the rate of more than $9 million a year, and that despite two fare increases.

Not long after arriving at the DSR, Davis concluded that "...the DSR had become a sloppily managed organization," and it

didn't take long to discover "the deplorable morale of the operation." He was appalled at the lackadaisical attitude of some

DSR people, and their lack of enthusiasm for their jobs. The morale problem became even more evident in the attitude of

the coach operators. In his autobiography, titled "One Man's Way," Davis wrote of one experience he had while visiting

one of the DSR terminals and talking with some of the drivers...

""I asked if they had taken a bus to work that day; they said none of them had. "The service is so bad,"

they explained, "we wouldn't ride the bus."

"Thank you, gentlemen," I said, smiled, and turned around. A Detroit Free Press reporter was standing

behind me, and turning to him, I remarked, "If someone had said something so negative to me about my

auto dealership, that man wouldn't have lasted long as an employee." That's all I said, and I just walk-

ed away."

Although Ed Davis inherited the problems facing the financially troubled and debt ridden bus system when he took over at

the helm, Davis was still determined that he could "sell" the public on DSR service, just as he had sold them Chryslers and

Plymouths. During his 2½ year reign as the general manager, Davis led the department through its waning years, during

both good times and bad. During the troublesome months of FY 1972-73 — when the DSR faced near bankruptcy, but

also during the more celebratory times — such as when the DSR celebrated its 50th Anniversary in May of 1972.

On October 1, 1971, about seven months after he closed his automobile dealership, Mayor Roman S. Gribbs appointed

Ed Davis as the new general manager of the DSR. At the time, Gribbs had been looking for a prominent black to join his

administration. It was hoped that Davis might discover some innovative ways to improve service at the problem-riddled,

money-losing transit agency. Davis later stated that he took the job as a challenge, and wanted to improve the system.

When Davis took over in October, 1971, the DSR operated 1,100 buses, employed 2,380 people, and generated more

than $200,000 from the fare box a day, or some $150 million a year. But despite those numbers, the department had

lost money every year since 1966, at the rate of more than $9 million a year, and that despite two fare increases.

Not long after arriving at the DSR, Davis concluded that "...the DSR had become a sloppily managed organization," and it

didn't take long to discover "the deplorable morale of the operation." He was appalled at the lackadaisical attitude of some

DSR people, and their lack of enthusiasm for their jobs. The morale problem became even more evident in the attitude of

the coach operators. In his autobiography, titled "One Man's Way," Davis wrote of one experience he had while visiting

one of the DSR terminals and talking with some of the drivers...

""I asked if they had taken a bus to work that day; they said none of them had. "The service is so bad,"

they explained, "we wouldn't ride the bus."

"Thank you, gentlemen," I said, smiled, and turned around. A Detroit Free Press reporter was standing

behind me, and turning to him, I remarked, "If someone had said something so negative to me about my

auto dealership, that man wouldn't have lasted long as an employee." That's all I said, and I just walk-

ed away."

Although Ed Davis inherited the problems facing the financially troubled and debt ridden bus system when he took over at

the helm, Davis was still determined that he could "sell" the public on DSR service, just as he had sold them Chryslers and

Plymouths. During his 2½ year reign as the general manager, Davis led the department through its waning years, during

both good times and bad. During the troublesome months of FY 1972-73 — when the DSR faced near bankruptcy, but

also during the more celebratory times — such as when the DSR celebrated its 50th Anniversary in May of 1972.

One innovative idea of Davis included a promotional "Ride the Bus Month" to

attract more riders, offering a 25¢ bus fare during certain hours of May, 1972,

to coincide with the DSR's 50th Anniversary on May 15th. The idea being

to change the public's mind about using public transit, by giving the DSR a

chance. It was also under Davis when a new fleet of 134 GMC air-conditioned

coaches arrived introducing the new DSR slogan, "Come Ride With Us!" It

was also Davis at the helm in 1972, when the new DSR administration offices

were opened at 1301 E. Warren. Ed Davis was also in charge in 1973, when

the first female bus drivers since WW-II were hired by the DSR. He was also

instrumental in promoting the first blacks as department heads in the DSR.

During his early months as general manager it wasn't unusual to find Ed Davis

riding the buses to "find out what's wrong." Davis demanded his department

heads also "get out of their offices and ride the buses,...and...take notes." He

added express service on such lines as Crosstown and Clairmount, so that

passengers wouldn't have to get off and transfer to get to work downtown.

Davis even envisioned exclusive bus lanes on the freeways, with a bus a min-

ute sailing downtown past cars stuck in traffic jams. He wanted to shout out

of the bus window to those drivers —"Come and ride with us. You'll get

there a lot sooner!"

Davis also had plans to alter a number of routes. His plans were to cut down

on services in the depopulated areas of the center city, and expand services

"where the people have gone," particularly in the northwest and northeast

sections beyond Grand Boulevard.

However, most of his ideas would have to take a back seat, as more pressing

financial problems lay ahead for the DSR. With drastic cuts in service on the

horizon, including the possible elimination of all Christmas and New Year's Day

service, and with the immanent possibility of bankruptcy being predicted for

the department, most of his ideas would never see the light of day.

Perhaps the most negative mark left on Davis' reign as general manager were

comments he made in March of 1972 regarding employee work performance.

|

A letter which Davis addressed to the Board of DSR Commissioners – later released to the press – made him a marked

man by the various DSR unions. In his letter Davis charged that the DSR was afflicted with high absenteeism on Mondays

and Fridays, stating that, "...in many positions, in excess of 20 percent of employees habitually take Friday and

Monday off." Davis also stated that the payment of phony sick claims and the high overtime necessary to cover those

absences, along with "accident-prone" drivers, and an accident claims racket, all constituted major expense items for the

department. Accident claims against the DSR were averaging about $100,000 a month, while unnecessary overtime was

costing more than $10,000 per month. Davis considered both to be unacceptable.

Of course, the charges were vehemently denied by union officials during a special news conference, where representatives

from the drivers' union, the salaried workers' union, the mechanics, and other department locals, were in attendance. The

head of AFSCME Council 77 even threatened a work stoppage, and demanded that Mayor Gribbs remove Davis from his

position. Although Davis was never released form his duties — which, no doubt, would have been an unwise political move

for the Mayor at that time in the city's history —- Davis, for the most part, maintained a low profile through the remainder

of his term. He did, however, manage to see the department through its financial situation, and remained on as the DSR's

general manager through the end of the Roman S. Gribbs administration. He resigned shortly after Coleman A. Young

was sworn in as mayor in January, 1974. That following July, under a newly revised City Charter, the DSR would become

the Detroit Department of Transportation (D-DOT).

Although Ed Davis would continue to receive many honors during his remaining years for his numerous accomplishments

in the auto industry — including being the first African-American inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1996 — not

much has been made over his short career as head of Detroit's ailing public transit system. A once proud system that had

been on a decline many years prior to the arrival of Ed Davis and would unfortunately continue on that decline for many

decades to come.

Edward "ED" Davis later passed away due to congestive heart failure on May 3, 1999, at the age of eighty-eight.

man by the various DSR unions. In his letter Davis charged that the DSR was afflicted with high absenteeism on Mondays

and Fridays, stating that, "...in many positions, in excess of 20 percent of employees habitually take Friday and

Monday off." Davis also stated that the payment of phony sick claims and the high overtime necessary to cover those

absences, along with "accident-prone" drivers, and an accident claims racket, all constituted major expense items for the

department. Accident claims against the DSR were averaging about $100,000 a month, while unnecessary overtime was

costing more than $10,000 per month. Davis considered both to be unacceptable.

Of course, the charges were vehemently denied by union officials during a special news conference, where representatives

from the drivers' union, the salaried workers' union, the mechanics, and other department locals, were in attendance. The

head of AFSCME Council 77 even threatened a work stoppage, and demanded that Mayor Gribbs remove Davis from his

position. Although Davis was never released form his duties — which, no doubt, would have been an unwise political move

for the Mayor at that time in the city's history —- Davis, for the most part, maintained a low profile through the remainder

of his term. He did, however, manage to see the department through its financial situation, and remained on as the DSR's

general manager through the end of the Roman S. Gribbs administration. He resigned shortly after Coleman A. Young

was sworn in as mayor in January, 1974. That following July, under a newly revised City Charter, the DSR would become

the Detroit Department of Transportation (D-DOT).

Although Ed Davis would continue to receive many honors during his remaining years for his numerous accomplishments

in the auto industry — including being the first African-American inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1996 — not

much has been made over his short career as head of Detroit's ailing public transit system. A once proud system that had

been on a decline many years prior to the arrival of Ed Davis and would unfortunately continue on that decline for many

decades to come.

Edward "ED" Davis later passed away due to congestive heart failure on May 3, 1999, at the age of eighty-eight.

SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT: I would like to personally thank DDOT Senior Service Inspector (SSI) Carl Dutch for loaning me his

copy of the Ed Davis autobiography "ONE MAN'S WAY" which was used to contribute information for this article. I do apologize to him

for keeping the book so long, but it was worth the time.

Information for the above article were compiled from numerous sources, including, the Ed Davis Autobiography "One Man's Way" (Ed Davis Associates, 1979),

the February 6, 1972 edition of the Detroit Free Press "Detroit Magazine" article titled, "Ed Davis: The Idealist in the Driver's Seat of the Creaky Old DSR,"

and also from miscellaneous 1972 thru 1973 Detroit Free Press and Detroit News newspaper articles (courtesy of the S. Sycko collection), and various online

sources, including the online web-site Answers.com: Ed Davis.

copy of the Ed Davis autobiography "ONE MAN'S WAY" which was used to contribute information for this article. I do apologize to him

for keeping the book so long, but it was worth the time.

Information for the above article were compiled from numerous sources, including, the Ed Davis Autobiography "One Man's Way" (Ed Davis Associates, 1979),

the February 6, 1972 edition of the Detroit Free Press "Detroit Magazine" article titled, "Ed Davis: The Idealist in the Driver's Seat of the Creaky Old DSR,"

and also from miscellaneous 1972 thru 1973 Detroit Free Press and Detroit News newspaper articles (courtesy of the S. Sycko collection), and various online

sources, including the online web-site Answers.com: Ed Davis.

| For Comments and/or Suggestions, Please contact Site Owner at: admin@detroittransithistory.info |

© 2007 (PAGE LAST MODIFIED ON 11-18-07)

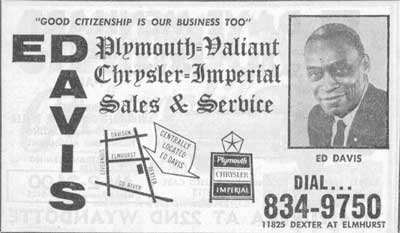

Finally, on November 11, 1963, Ed Davis was able to

secure a new-car franchise with Chrysler-Plymouth

—making him the first African-American to be award-

ed a "Big Three" auto franchise. His Ed Davis, Inc.,

Plymouth-Chrysler-Imperial Dealership (Dealer

Number 62399) was located in a predominately black

middle-class neighborhood, at 11825 Dexter Avenue

at Elmhurst, on the city's west-side.

The Davis dealership prospered immediately and had

to be enlarged within its first few years. It grew to be-

come one of Chrysler Corporation's most aggres-

sive dealerships, selling an average of 1,000 new cars

and twice that figure in used cars a year.

secure a new-car franchise with Chrysler-Plymouth

—making him the first African-American to be award-

ed a "Big Three" auto franchise. His Ed Davis, Inc.,

Plymouth-Chrysler-Imperial Dealership (Dealer

Number 62399) was located in a predominately black

middle-class neighborhood, at 11825 Dexter Avenue

at Elmhurst, on the city's west-side.

The Davis dealership prospered immediately and had

to be enlarged within its first few years. It grew to be-

come one of Chrysler Corporation's most aggres-

sive dealerships, selling an average of 1,000 new cars

and twice that figure in used cars a year.

| (Detroit phone-book advertisement courtesy of DetroitYES.com) |

| DETROIT TRANSIT HISTORY |

| DETROIT TRANSIT HISTORY |

(NOTE:

Page best viewed using Internet Explorer browser - Other browsers used

with Macintosh computers may distort the page layout.)

| The web-site which takes a look back at the History of Public Transportation in and around the City of Detroit. |

| .. |

But by the time of the 1967 Detroit riots, the neighborhood surrounding his dealership had changed, from middle class to

one of the toughest on the West Side. Davis soon found theft from his lot an impossible problem, as was also the inability

to obtain insurance. Requests by Davis in 1968 to relocate his business to the city's northwest section — where the black

middle-class was headed — were denied after Chrysler was unwilling to undertake such a project. After his employees and

salesmen unionized in 1969, and the ongoing union labor problems that followed, Ed Davis decided to close his dealership

after thirty-plus years in the automobile business. Later, Davis was quoted as saying, "Finally, it reached the point where it

wasn't worth it anymore." On February 26, 1971, Ed Davis retired, and closed the doors to his auto dealership business.

one of the toughest on the West Side. Davis soon found theft from his lot an impossible problem, as was also the inability

to obtain insurance. Requests by Davis in 1968 to relocate his business to the city's northwest section — where the black

middle-class was headed — were denied after Chrysler was unwilling to undertake such a project. After his employees and

salesmen unionized in 1969, and the ongoing union labor problems that followed, Ed Davis decided to close his dealership

after thirty-plus years in the automobile business. Later, Davis was quoted as saying, "Finally, it reached the point where it

wasn't worth it anymore." On February 26, 1971, Ed Davis retired, and closed the doors to his auto dealership business.

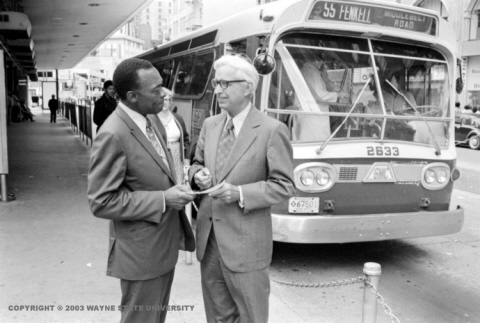

| In this August, 1973 photo, DSR general manager Ed Davis (l.) is seen conversing with SEMTA general manager Thomas H. Lipscomb, while out-side of the old DSR Capitol Park loading station. Some at the time felt that Ed Davis would basically preside over the liquidation sale of the DSR, which many felt would soon be absorbed by the regional Southeastern Michigan Transportation Authority (SEMTA) (Photo courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University) Virtual Motor City Collection photo #37057_1, used by permission of the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. All rights, including those of further reproduction and/or publication, are reserved in full by the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Photographic reproductions may be protected by U.S. copyright law (U.S. Title 17). The user is fully responsible for copyright infringement. |

| Click here to return to the "AROUND OLD DETROIT" Main Page. |