Want to have some fun at the next car show?

Cruise through the rows until you find a bellybutton car-that is, a car you can't attend a show without seeing. Fifty-seven Chevy or a Model A perhaps. Then find the owner and ask why he chose to build that particular car. More often than not, he will tell you it was the easiest car to restore. "Yeah, I didn't want an off-brand car because you can't find any parts for them," he'll likely say.

At that point, you can tell him all about Bill Cathcart, of Plainfield, Connecticut, and how simple he makes it seem to build and run a flathead Studebaker six-cylinder engine. After all, if somebody out there specializes in a subject that far off the beaten path, you know that discontinued "off-brand" independent makes still have a good amount of life left in them.

Bill, as one may expect, is one of the few persons left in the country who knows his way around a Studebaker straight-six. Since retiring more than a dozen years ago from his position as a repair garage supervisor for the State of Connecticut, he's kept himself busy not only with his mail-order business selling NOS Studebaker parts, but also with building both stock and high-performance Studebaker sixes and with developing and selling new and vintage high-performance parts for those engines.

As one may also expect, Bill isn't exactly running a multi-million-dollar, multi-thousands-square-foot business by staking out such a niche market. Rather, he works out of his own two-bay garage attached to the house. A partition separates both bays, leaving one for the dirty work-welding, grinding and car assembly-and the other for the tasks that require a little less grit floating in the air-engine assembly, primarily.

A 170-cu.in. Champion flathead six hangs bolted to an engine stand, waiting for a crankshaft, pistons, valves and cylinder head. An oven sits along the partition, useful for getting cast-iron pieces up to a suitable welding temperature as well as for heating the shop during cold New England winters. Hand-written labels mark the contents of each of the drawers and bins lining another two walls. A group of spare crankshafts stand properly stored on their ends, neatly out of the way. The garage décor includes a healthy mix of stock-car racing posters, Studebaker memorabilia and old advertisements-apparently whatever strikes Bill's fancy.

Bill's green hot-rodded 1960 Lark fills the majority of the dirty work bay. The engine lies exposed with the hood off, making it much easier for Bill to work on the car. Outside sits another Studebaker, a 1963 Lark, and the lean-to beside the shed hosts a small mountain of six-cylinder cores and assorted fans, headers and other parts.

Bill said his affliction with the cars from South Bend started in 1965, when he got his job with the state. As Bill described it, he "didn't have a pot to piss in," so, in search of inexpensive, basic daily transportation, he found a low-mileage 1959 Lark in a used-car lot on special for $300. "I drove the hell out of that car," Bill said. "It was dependable and easy to maintain, though."

So, when in search of a replacement about five years later, he looked for, and found, another Studebaker-this time, a 1960 Lark station wagon, the only V-8-powered Studebaker he's driven. While in search of spare parts, he came across a number of dealerships and collectors looking to liquidate their parts piles, including one in the Boston area chock full of parts.

"There were cellars and attics full of chrome," Bill said. "I found five sets of NOS Avanti chrome valve covers, two complete cars in the garage, engines and transmissions stacked three feet high, Hawk sheetmetal in the cellar and a brand-new R1 engine still in the crate. It took seven loads full to get it all out of there."

Over the next decade or so, Bill continued to accumulate NOS parts as they became available from defunct Studebaker dealers. In 1985, he decided to start selling off those parts, along with some remanufactured parts he began to buy from a wholesaler, under his newly formed business, Cathcart Studebaker. As the NOS supply has since dried up, the business has shifted to offer almost exclusively remanufactured parts, but Bill said he can't believe how much NOS stuff remains. "Every once in a while, a dealer will pop up that has held on to this stuff for years and years," Bill said.

For example, tucked into a corner of his shop sits what Bill believes to be the last remaining NOS flathead Studebaker six-cylinder block. It sits on end, with no near-future plans for running it. Bill said it came from a parts house in South Bend that likewise had it tucked away, though nobody knew of it until a fellow Studebaker enthusiast bought the entire contents of the warehouse.

Yet, despite a network of parts dealers and a couple of closely guarded Studebaker-specific junkyards, it's not exactly simple to obtain everything you need to build one of these cars. Bill specifically cites clutch discs and electronic parts as the toughest to locate.

The engine-building side of the business started at an equally unintentional pace. After a friend asked him to rebuild a flathead six, he took on a couple more rebuilds, then eventually decided to advertise that service as well. Bill said he now builds about six engines a year, one at a time, and despite the wide range of engine rebuild options he gives his customers, he generally builds his engines for both power and reliability. "These things are like a tractor engine," he said. "If they're in good shape, you can't hurt them."

Each engine he builds completely to the customer's tastes, from 90hp stone stockers up to outrageous (for a Studebaker flathead six) 140hp naturally aspirated, non-stroked, multi-carbureted fire-breathers. Prices range from $2,800 for a basic rebuild to as much as $4,300 for the heavy hitters.

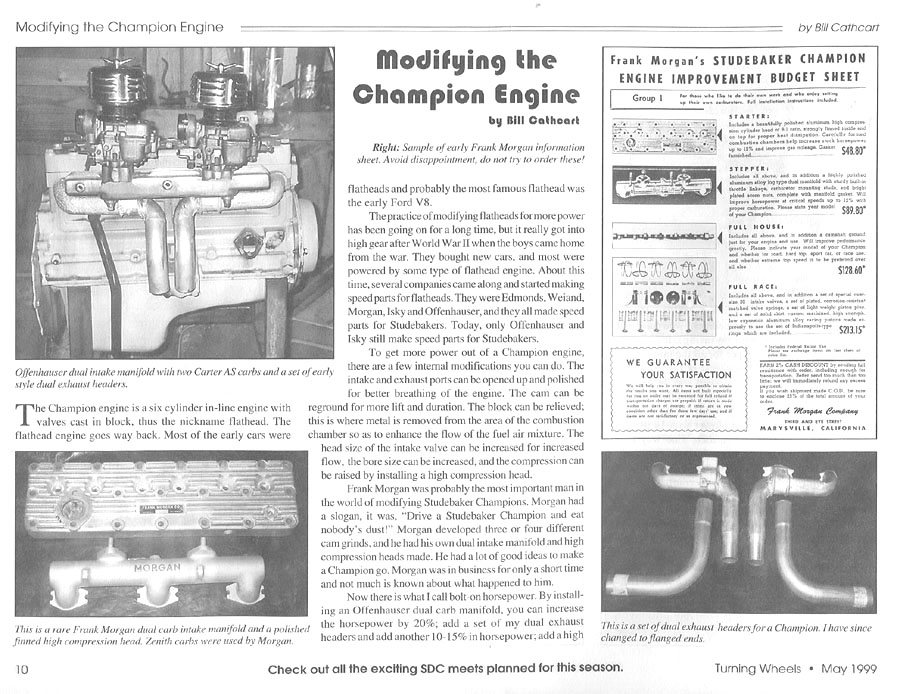

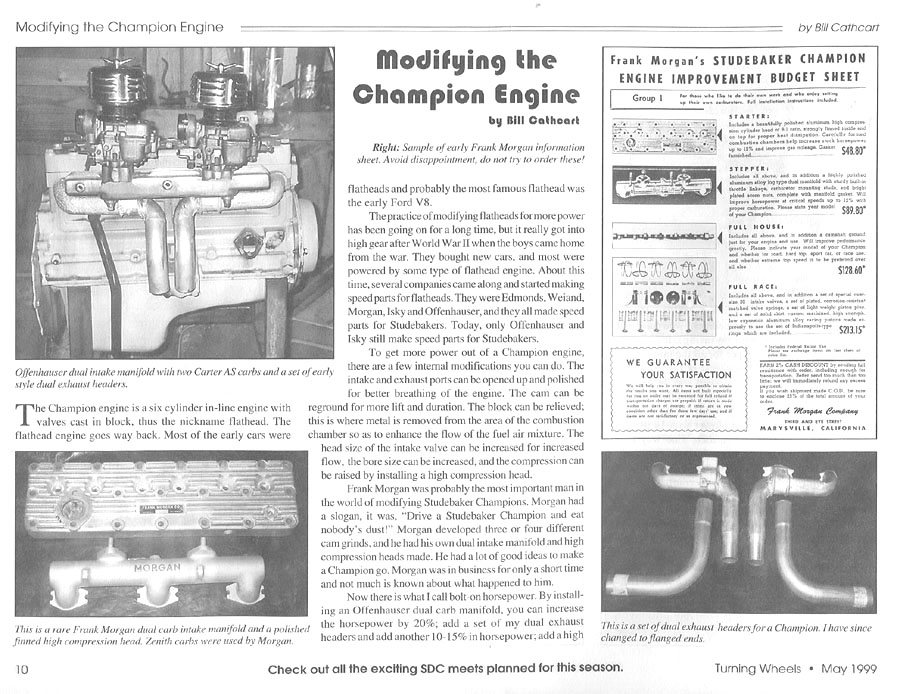

Bill said he finds the engines fairly simple to work on and rather similar to the flathead Ford V-8s, straight-sixes and inline-fours. Studebaker built the Champion engines, which generally displaced about 170 cubic inches, and the Commander engines, which generally displaced about 226 cubic inches, in various forms back to the 1930s and through to 1961, when the company dropped the flathead in favor of a new overhead-valve design.

Bill will defend the much-maligned flathead as a decent, strong, dependable engine, but he also will admit that Studebaker screwed up by waiting so long to develop the more modern OHV six-cylinder for 1961, just three short years before the company dropped all of its own engines in favor of the Chevrolet straight-sixes and V-8s that powered the last-gasp 1965 and 1966 cars. "The L-head engine was obsolete for a long, long time, and I think that hurt them in sales," he said. "The body design was legendary, but the engine just couldn't keep up."

Which is likely why most Studebaker enthusiasts turn to the OHV V-8s, which donated a good deal of parts and technology to the OHV straight-six. Bill notes that the OHV straight-sixes, which he rebuilds on occasion, shared much of the bottom end with the flathead sixes, but Studebaker revised the blocks and structure of the engines enough to make it impossible to convert a flathead to OHV simply by bolting on a newer cylinder head.

As for the speed parts, Bill said Offenhauser still makes a dual-carburetor intake manifold, for which Bill constructs a throttle linkage system. Bill has also teamed with a fellow Studebaker enthusiast, Ben Ordas in Indiana, to remanufacture a finned aluminum high-compression cylinder head made popular in the early 1950s by a man named Frank Morgan. According to Bill, Morgan mysteriously stopped production and left no trace of his existence after about 1957 or 1958, making research on the original heads fairly difficult. Nevertheless, Bill and Ben came up with a similar design that incorporates a few changes, including a bump in compression ratio from 7.5:1 to 8.5:1.

Bill has also engineered an adapter that will allow these engines to mate to a modern Borg-Warner T-5 manual transmission. He said many folks running these engines, especially in the trucks with 4.88:1-geared rear axles, have clamored for years for some sort of overdrive transmission. "With a T-5, you can gain about 20 mph, and you can at least drive on the Turnpike at a reasonable speed," Bill said.

Bill said the engines generally don't respond too well to stroking-which can put the tops of the pistons above the block-or to power-adders like superchargers and turbochargers. He sticks largely with upgrading the ignitions and the lifters (which are prone to excessive wear) and maintaining backpressure via small-diameter exhaust systems. And as much as one can increase the compression or bore these engines out (Bill sticks with .060 overbores, but said he can go out to .125 with good, solid blocks), they tend to develop all their power between 2,750 and 3,000 rpm.

The popularity of flathead sixes doesn't seem anywhere near waning, Bill said. "I think it'll continue to stay around," he said. "There are tons and tons of Champions still out there." The near-even balance between customers who want stock, mild and wild engines doesn't seem to be headed toward a tipping point anytime soon.

And Bill, at 67 years old, doesn't seem ready to give up the business either.

"I'm going to keep doing this as long as I can," he said.

his article originally appeared in the JANUARY 1, 2005 issue of Hemmings Classic Car.